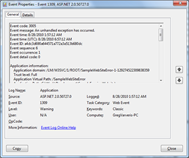

Sometimes a customer will ask me to look at their site and make some recommendations on what can be improved. One of the many things I’ll look at is their event logs. One of the nice things about ASP.NET is that when you encounter an unhandled exception, an event will be placed into your Application event log. The message of the event log entry will usually include lots of good stuff like the application, path, machine name, exception type, stack trace, etc. Loads of great stuff and all for free. For customers that don’t have a centralized exception logging strategy, this can be a gold mine.

Sometimes a customer will ask me to look at their site and make some recommendations on what can be improved. One of the many things I’ll look at is their event logs. One of the nice things about ASP.NET is that when you encounter an unhandled exception, an event will be placed into your Application event log. The message of the event log entry will usually include lots of good stuff like the application, path, machine name, exception type, stack trace, etc. Loads of great stuff and all for free. For customers that don’t have a centralized exception logging strategy, this can be a gold mine.

The way it usually works is that they will provide me an EVTX from their servers. If you’re not aware, an EVTX is just an archive of the events from the event log you specify. By itself, looking at the raw event logs from a server can be quite daunting. There are usually thousands of entries in the event log and filtering down to what you actually care about can be exhausting. Even if you do find a series of ASP.NET event log messages, the problem has always been – how do you take all of this great information that’s just dumped into the Message property of the event log entry and put it into a format you can easily report on, generate statistics, etc. Fortunately, I have a non-painful solution.

I’ve broken this down into a relatively simple 4-step process:

- Get the EVTX

- Generate a useful XML file

- Parse into an object model

- Analyze and report on the data

Let’s get to it.

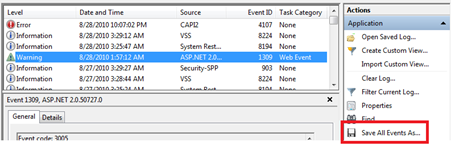

Step 1: Get the EVTX

This step is pretty short and sweet. In the Event Log manager, select the “Application” group and then select the “Save All Events As…” option.

That will produce an EVTX file with whatever name you specify. Once you have the file, transfer it to your machine as you generally do not want to install too many tools in your production environment.

Step 2: Generate a useful XML file

Now that we have the raw EVTX file, we can get just the data we care about using a great tool called LogParser. Jeff Atwood did a nice little write-up on the tool but simply put it’s the Swiss Army knife of parsing tools. It can do just about anything data related you would wish using a nice pseudo-SQL language. We’ll use the tool to pull out just the data from the event log we want and dump it into an XML file. The query that we can use for this task is daunting in its simplicity:

SELECT Message INTO MyData.xml

FROM ‘*.evtx’

WHERE EventID=1309

The only other thing we need to tell LogParser is the format in which it the data is coming in and the format to put it into. This makes our single command the following:

C:\>logparser -i:EVT -o:XML

"SELECT Message INTO MyData.xml FROM ‘*.evtx’ WHERE EventID=1309"

This will produce a nice XML file that looks something like the following:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="ISO-10646-UCS-2" standalone="yes" ?>

<ROOT DATE_CREATED="2010-08-29 06:04:20" CREATED_BY="Microsoft Log Parser V2.2">

<ROW>

<Message>Event code: 3005 Event message: An unhandled exception has occurred...

</Message>

</ROW>

...

</ROOT>

One thing that you may notice is that all of the nicely formatted data from our original event log message is munged together into one unending string. This will actually work in our favor but more on that in the next step.

Step 3: Parse into an object model

So, now that we have an XML file with all of our event details, let’s do some parsing. Since all of our data is in one string, the simplest method is to apply a RegEx expression with grouping to grab the data we care about.

In a future post, I’ll talk about a much faster way of getting this type of data without a RegEx expression. After all, refactoring is a way of life for developers.

private const string LargeRegexString = @"Event code:(?<Eventcode>.+)" +

@"Event message:(?<Eventmessage>.+)" +

@"Event time:(?<Eventtime>.+)" +

@"Event time \(UTC\):(?<EventtimeUTC>.+)" +

@"Event ID:(?<EventID>.+)" +

@"Event sequence:(?<Eventsequence>.+)" +

@"Event occurrence:(?<Eventoccurrence>.+)" +

@"Event detail code:(?<Eventdetailcode>.+)" +

@"Application information:(?<Applicationinformation>.+)" +

@"Application domain:(?<Applicationdomain>.+)" +

@"Trust level:(?<Trustlevel>.+)" +

@"Full Application Virtual Path:(?<FullApplicationVirtualPath>.+)" +

@"Application Path:(?<ApplicationPath>.+)" +

@"Machine name:(?<Machinename>.+)" +

@"Process information:(?<Processinformation>.+)" +

@"Process ID:(?<ProcessID>.+)" +

@"Process name:(?<Processname>.+)" +

@"Account name:(?<Accountname>.+)" +

@"Exception information:(?<Exceptioninformation>.+)" +

@"Exception type:(?<Exceptiontype>.+)" +

@"Exception message:(?<Exceptionmessage>.+)" +

@"Request information:(?<Requestinformation>.+)" +

@"Request URL:(?<RequestURL>.+)" +

@"Request path:(?<Requestpath>.+)" +

@"User host address:(?<Userhostaddress>.+)" +

@"User:(?<User>.+)" +

@"Is authenticated:(?<Isauthenticated>.+)" +

@"Authentication Type:(?<AuthenticationType>.+)" +

@"Thread account name:(?<Threadaccountname>.+)" +

@"Thread information:(?<Threadinformation>.+)" +

@"Thread ID:(?<ThreadID>.+)" +

@"Thread account name:(?<Threadaccountname>.+)" +

@"Is impersonating:(?<Isimpersonating>.+)" +

@"Stack trace:(?<Stacktrace>.+)" +

@"Custom event details:(?<Customeventdetails>.+)";

Now that we have our RegEx, we’ll just write the code to match it against a string and populate our class. While I’ve included the entire regex above, I’ve only included a partial implementation of the class population below.

public class EventLogMessage

{

private static Regex s_regex = new Regex(LargeRegexString, RegexOptions.Compiled);

public static EventLogMessage Load(string rawMessageText)

{

Match myMatch = s_regex.Match(rawMessageText);

EventLogMessage message = new EventLogMessage();

message.Eventcode = myMatch.Groups["Eventcode"].Value;

message.Eventmessage = myMatch.Groups["Eventmessage"].Value;

message.Eventtime = myMatch.Groups["Eventtime"].Value;

message.EventtimeUTC = myMatch.Groups["EventtimeUTC"].Value;

message.EventID = myMatch.Groups["EventID"].Value;

message.Eventsequence = myMatch.Groups["Eventsequence"].Value;

message.Eventoccurrence = myMatch.Groups["Eventoccurrence"].Value;

...

return message;

}

public string Eventcode { get; set; }

public string Eventmessage { get; set; }

public string Eventtime { get; set; }

public string EventtimeUTC { get; set; }

public string EventID { get; set; }

public string Eventsequence { get; set; }

public string Eventoccurrence { get; set; }

...

}

The last step is just to read in the XML file and instantiate these objects.

XDocument document = XDocument.Load(@"<path to data>\MyData.xml");

var messages = from message in document.Descendants("Message")

select EventLogMessage.Load(message.Value);

Now that we have our objects and everything is parsed just right, we can finally get some statistics and make sense of the data.

Step 4: Analyze and report on the data

This last step is really the whole point of this exercise. Fortunately, now that all of the data is an easily query’able format using our old friend LINQ, the actual aggregates and statistics are trivial. Really, though, everyone’s needs are going to be different but I’ll provide a few queries that might be useful.

Query 1: Exception Type Summary

For example, let’s say you wanted to output a breakdown of the various Exception Types in your log file. The query you would use for that would be something like:

var results = from log in messages

group log by log.Exceptiontype into l

orderby l.Count() descending, l.Key

select new

{

ExceptionType = l.Key,

ExceptionCount = l.Count()

};

foreach (var result in results)

{

Console.WriteLine("{0} : {1} time(s)",

result.ExceptionType,

result.ExceptionCount);

}

This would then output something like:

WebException : 15 time(s)

InvalidOperationException : 7 time(s)

NotImplementedException : 2 time(s)

InvalidCastException : 1 time(s)

MissingMethodException : 1 time(s)

Query 2: Exception Type and Request URL Summary

Let’s say that you wanted to go deeper and get the breakdown of which URL’s generated the most exceptions. You can just expand that second foreach loop in the above snippet to do the following:

foreach (var result in results)

{

Console.WriteLine("{0} : {1} time(s)",

result.ExceptionType,

result.ExceptionCount);

var requestUrls = from urls in messages

where urls.Exceptiontype == result.ExceptionType

group urls by urls.RequestURL.ToLower() into url

orderby url.Count() descending, url.Key

select new

{

RequestUrl = url.Key,

Count = url.Count()

};

foreach (var url in requestUrls){

Console.WriteLine("\t{0} : {1} times ",

url.RequestUrl,

url.Count);

}

}

This then would produce output like this:

WebException : 15 time(s)

http://localhost/menusample/default.aspx : 11 times

http://localhost:63188/menusample/default.aspx : 4 times

InvalidOperationException : 7 time(s)

http://localhost:63188/menusample/default.aspx : 6 times

http://localhost/menusample/default.aspx : 1 times

NotImplementedException : 2 time(s)

http://localhost/samplewebsiteerror/default.aspx : 2 times

InvalidCastException : 1 time(s)

http://localhost:63188/menusample/default.aspx : 1 times

MissingMethodException : 1 time(s)

http://localhost:63188/menusample/default.aspx : 1 times

Query 3: Exception Type, Request URL and Method Name Summary

You can even go deeper, if you so desire, to find out which of your methods threw the most exceptions. For this to work, we need to make a slight change to our EventLogMessage class to parse the Stack Trace data into a class. First, we’ll start with our simple little StackTraceFrame class:

public class StackTraceFrame

{

public string Method { get; set; }

}

Second, add a new property to our EventLogMessage class to hold a List<StackTraceFrame>:

public List<StackTraceFrame> StackTraceFrames { get; set; }

Lastly, add a method (and its caller) to parse out the stack frames and assign the resulting List to the StackTraceFrames property mentioned above:

public EventLogMessage(string rawMessageText)

{

Match myMatch = s_regex.Match(rawMessageText);

...

Stacktrace = myMatch.Groups["Stacktrace"].Value;

...

StackTraceFrames = ParseStackTrace(Stacktrace);

}

private List<StackTraceFrame> ParseStackTrace(string stackTrace)

{

List<StackTraceFrame> frames = new List<StackTraceFrame>();

string[] stackTraceSplit = stackTrace.Split(new string[] { " at " },

StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries);

foreach (string st in stackTraceSplit)

{

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(st))

{

frames.Add(new StackTraceFrame() { Method = st });

}

}

return frames;

}

Please Note: You could enhance the ParseStackTrace(…) method to parse out the source files, line numbers, etc. I’ll leave this as an exercise for you, dear reader.

Now that we have the infrastructure in place, the query is just as simple. We’ll just nest this additional query inside of our URL query like so:

foreach (var url in requestUrls){

Console.WriteLine("\t{0} : {1} times ",

url.RequestUrl,

url.Count);

var methods = from method in messages

where string.Equals(method.RequestURL,

url.RequestUrl,

StringComparison.InvariantCultureIgnoreCase)

&&

string.Equals(method.Exceptiontype,

result.ExceptionType,

StringComparison.InvariantCultureIgnoreCase)

group method by method.StackTraceFrames[0].Method into mt

orderby mt.Count() descending, mt.Key

select new

{

MethodName = mt.Key,

Count = mt.Count()

};

foreach (var method in methods)

{

Console.WriteLine("\t\t{0} : {1} times ",

method.MethodName,

method.Count

);

}

}

This would then produce output like the following:

WebException : 15 time(s)

http://localhost/menusample/default.aspx : 11 times

System.Net.HttpWebRequest.GetResponse() : 11 times

http://localhost:63188/menusample/default.aspx : 4 times

System.Net.HttpWebRequest.GetResponse() : 4 times

InvalidOperationException : 7 time(s)

http://localhost:63188/menusample/default.aspx : 6 times

System.Web.UI.WebControls.Menu... : 6 times

http://localhost/menusample/default.aspx : 1 times

System.Web.UI.WebControls.Menu... : 1 times

One last thing you may notice is that the in the example above, the first frame for each of those exceptions are somewhere in the bowels of the .NET BCL. You may want to filter this out even further to only return YOUR method. This can be accomplished very easily with the method below. It will simply loop through the StackTraceFrame List and return the first method it encounters that does not start with “System.” or “Microsoft.”.

private static string GetMyMethod(List<StackTraceFrame> frames)

{

foreach (StackTraceFrame frame in frames)

{

if (!frame.Method.StartsWith("System.") &&

!frame.Method.StartsWith("Microsoft."))

return frame.Method;

}

return "No User Code detected.";

}

Then, you can just call that method from the new query we wrote above:

var methods = from method in messages

where ...

group method by

GetMyMethod(method.StackTraceFrames) into mt

...

Finally, with this new snippet in place, we’ll get output like this:

WebException : 15 time(s)

http://localhost/menusample/default.aspx : 11 times

_Default.Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs e)...: 8 times

No User Code detected. : 3 times

http://localhost:63188/menusample/default.aspx : 4 times

_Default.Page_Load(Object sender, EventArgs e)... : 1 times

No User Code detected. : 1 times

WebControls.CustomXmlHierarchicalDataSourceView.Select()... : 2 times

As you can see, the sky’s the limit.

Enjoy!